Section E New Testament

Chapter 38 - Western Wall Tunnels

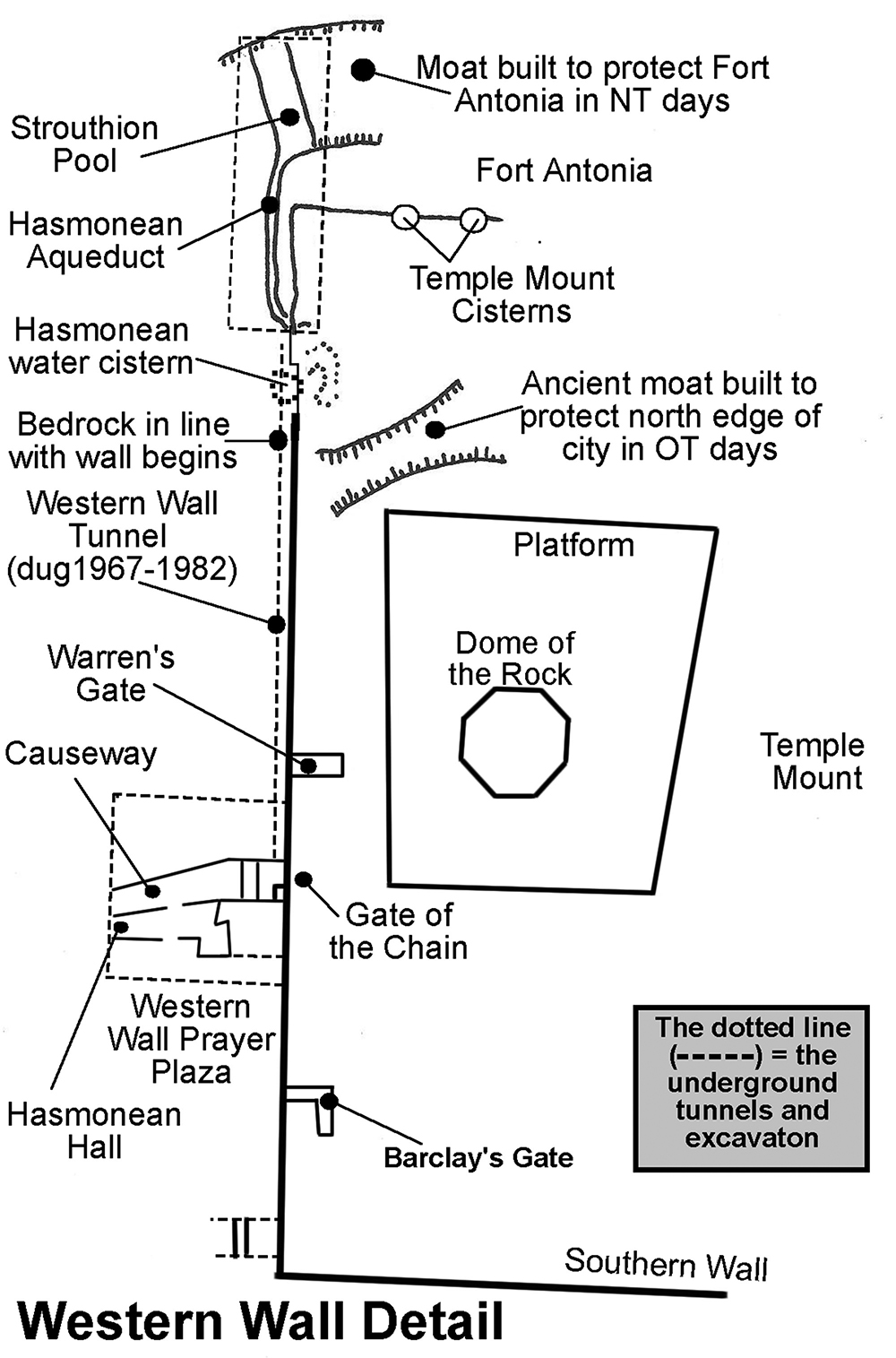

When Herod doubled the size of the Old Testament Temple Mount he expanded to the north, to the south and to the west. The walls along the west side were set on the bedrock. The west wall of the Temple Mount’s retaining wall is 1,591 feet long, making it the longest of the four Temple Mount walls. In 70 AD the Romans completely destroyed the Temple, the Temple Mount buildings, and most of the Temple Mount wall except for the lower portions that were buried in the rubble from the debris of the dismantled Temple precincts and walls above. From the Western Wall Prayer Plaza beside Wilson’s Arch a tunnel can be entered that runs along the northern portion of the west wall up to its northwest corner.

A vaulted passageway entered from the Western Wall Prayer Plaza. It leads to Wilson’s Arch and the tunnels along the northern portion of the Western Wall.

The Master Course Stone: This stone is 44 feet long, 11.5 feet high, and 15 feet wide. It is estimated to weigh 570-630 tons. This stone is the master course. It was used to stabilize the smaller stones under it. It sits 20 feet above the Herodian street level and 33 feet above the bedrock. The master course extends to the left of the edge of this photo and past the right edge. The small stones setting above were used to fill in where the Romans chipped away at it in 70 AD, attempting to dismantle the whole Western Wall. They reached the level of this Master Course Stone and stopped. The rectangular holes in the stone were bored centuries later to help secure plaster to the wall in order to create an underground cistern to hold water for the homes above.

Another view of the Master Course Stone.

Galyn in the Western Wall tunnels by largest Herodian ashlar in the Temple Mount walls.

The rectangle holes in the ashlar were cut around 135 AD when Hadrian converted this area under the rubble into cisterns. The rectangle holes where cut so that wooden blocks or stones could be inserted into them to help secure the plaster to the walls. The plaster made the walls of the cisterns watertight. Some plaster can still be seen attached to part of the wall.

A close look at the ashlar with the wooden (stone) block holding the plaster in place in the Western Wall tunnel.

Looking north down the long Western Wall Tunnel.

This is a photo of Warren's Gate that was used to access the Temple Mount. Notice the decorative engraving on the door jamb on the right side of the photo (the straight groove beginning by the number 12). Warren’s Gate is about 150 feet into the Western Wall Tunnel. The paving stones are from the original Herodian street that led to this gate. On the other side of this blocked gateway is a stairway under the Temple Mount leading up to the Temple Mount surface, which the Jews used in the Middle Ages as a synagogue called “The Cave.”

Maimonides wrote in The Book of Temple Service in the 1100’s: “When Solomon built the Temple, knowing that it was destined to be destroyed, he built underneath, in deep and winding tunnels, a place in which to hide the Ark. It was King Josiah who commanded the Ark be hidden in the place which Solomon had prepared.” Second Chronicles 35:3 might refer to Josiah removing the Ark of the Covenant from the Temple to the hiding place Solomon had made, before the Babylonian invasion: “And he said to the Levites who taught all Israel and who were holy to the Lord, ‘Put the holy ark in the house that Solomon the son of David, king of Israel, built.”

Just a few feet north of Warren’s Gate is an area with an arch that is directly west of the Holy of Holies where the Ark of the Covenant sat. This is the closest the Jews can get to the Holy of Holies today. Warren’s Gate can be seen on the right edge of this photo just down the steps. The pavement in this photo is original Herodian.

The tunnel continues further and further to the north along the Western Wall.

This photo was taken from the tunnel along the Western Wall looking down into an excavated area of the wall. (The Western Wall is to the top of the photo.) This view shows how deep the courses of ashlar stones go before they reach bedrock.

Another view looking down at the ashlars. Details of the preserved stones show the quality of workmanship that is not seen on stones that have been exposed to wars and elements for 2,000 years. Notice, the depth is not as great as before since the bedrock level rises the further north the tunnel goes.

More tunnel and more ashlars as we continue toward the north.

A Herodian street near the north end of the Western Wall tunnels. The two pillars on the left were part of a colonnaded street that ran to the west of this street. This photo was taken looking north with the Western Wall on the right. This Herodian street would have run north-to-south, and the colonnaded street would have made a “T” intersection with it and run toward the west (left).

Galyn at the “T” intersection of the Herodian street at the north end of the Western Wall tunnels.

This quarry, only a few feet north of the Herodian road and the Hasmonean cistern, is where most of the Herodian stones for the Western Wall were taken from.

This is the Hasmonean Aqueduct cut through bedrock. It goes to the pool on the northwest corner of the western wall of the Temple Mount. The bedrock walls have been worn smooth by the water.

Toni stands on the Herodian pavement between two pillars that are part of the road that led to the left of the picture. 2,000 years ago this area was under open sky, and the road continued straight (north) and to the left (west). Other pillars going west have been excavated further down the road that would have been in line with these two pillars.

Toni stands by an unfinished quarried stone. Wooden blocks would have been wedged into the groove in the middle and then soaked with water to make the stone split.

The tunnels continue through the Hasmonean aqueduct to the cisterns on the northwest corner of the Temple Mount.

North of the Western Wall and Temple Mount

In 1996 Benjamin Netanyahu allowed the Jews to open the northern end of this Western Wall tunnel. When the tunnel was blasted through, it opened onto the Ummariya Madrasah, which is the street adjacent to the Via Dolorosa. This action resulted in riots by the Muslims who believed that the Jews were tunneling under the Temple Mount and that they were attempting to lay claim to the area of territory in the Muslim Quarter (which is, either way, in Israel and under Israeli control). Over the next two weeks 14 people were killed in the riots protesting the opening of the north end of the Western Wall Tunnel. Today a wall has been built across the north end of the tunnel. The Tunnel must now be accessed from the north side in the Convent of the Sisters of Zion. The Struthion Pool lies below this covenant.

Walking through a water system that Herod redirected to the Temple Mount.

The Struthion Pool was an open pool that served as a water reservoir for the city and as a moat for Fort Antonia. It collected rain water and also received water from the Hasmonean aqueduct.

The vaulted ceiling installed by Hadrian in 135 to cover the open pools of water. The holes in the roof where used by people above to access the water by lowering buckets on ropes. Hadrian built a market place at street level above these vaulted ceilings.